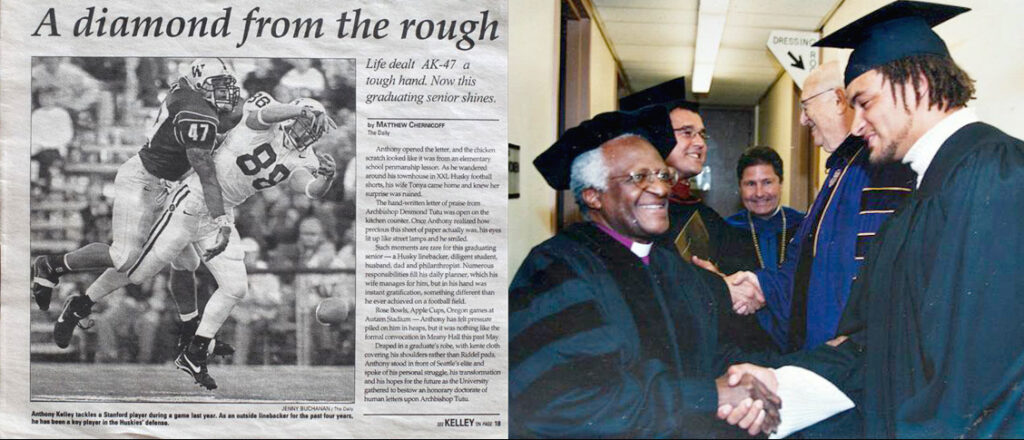

Anthony Featured in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer: UW’s Kelley matures into solid student-athlete

UW’s Kelley matures into solid student-athlete

Football player returns the favor of lessons learned in South Africa

http://www.seattlepi.com/news/article/UW-s-Kelley-matures-into-solid-student-athlete-1089173.php

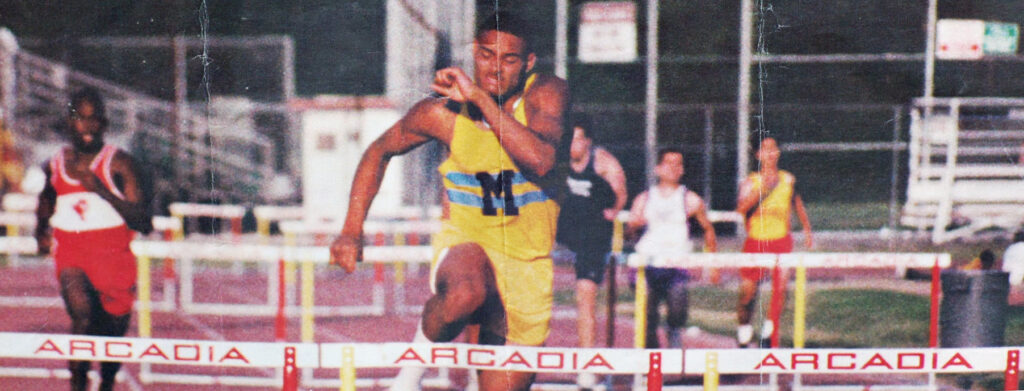

As a football player, Anthony Kelley looked like a can’t-miss talent coming out of high school in Pasadena, Calif. After a standout senior season, he was courted by national college powerhouses Nebraska and Michigan before deciding to play for the University of Washington.

But as a student, his prospects seemed murky at best. After bouncing among three high schools in Michigan and California, Kelley lacked the minimum academic credentials required for football recruits by national college rules. He was admitted to the UW in 1998 as a “partial qualifier,” meaning he’d have to prove his mettle in the classroom before taking the field.

On Saturday, Kelley will graduate from the UW with a degree in the comparative history of ideas, capping four years of studies that included extra scholarships and a leadership award.

Along the way, he’s earned three varsity letters as a football linebacker.

But Kelley credits the lessons he learned studying in South Africa for changing him into much more than “AK-47,” the nickname he picked up as a “lethal” linebacker wearing that number on his football uniform.

“It made me put football into a whole different perspective,” Kelley said of his overseas experience. “It’s just a game. There’s more to life than being a great football player.”

Even as he wrapped up his schoolwork before graduation, Kelley thrashed out the logistics of a flight to Seattle by a dance troupe of 12 South African girls from Inshinga Primary School in Guguletu, a township outside Cape Town. Kelley organized the trip and raised money for it after working with the school during the UW’s winter quarters in 2001 and 2002.

Kelley’s role in arranging the dance trip reflects “a level of commitment I rarely see in any undergraduate,” said Kari Tupper, acting director of the comparative history of ideas program, which co-ordinated the South Africa studies.

The girls will perform at the Paramount Theater, Children’s Hospital and university events. Kelley will introduce them at a news conference today at the UW.

“He’s an impressive person, with a very high level of commitment to doing what he says he’ll do and doing the best job he can,” Tupper said. “In any student, that would be remarkable; for a student with sort of the marginal record on which he was admitted, it’s exceptional.

“He’s funny, he’s warm, he’s articulate — he’s really been sort of a gift to us.”

Kelley said he was diagnosed at an early age with attention deficit disorder, but his family’s frequent moves meant he never received treatment. His mother and father split up a year after he was born, and he lived with his mother, mostly in Southern California and later in Michigan.

Sometimes, Kelley and his mother relied on public assistance; he remembers a brief stretch when they lived out of their car in San Diego.

It was when he was in high school in Michigan that his athletic talent emerged unmistakably, and his parents decided he should move in with his father in Pasadena to concentrate on sports.

“My life was basically one-sided,” Kelley said. “It was all athletics.

“I wasn’t very good in school. It was more a hassle.”

And when he wasn’t playing sports, he was skating on the edge of gang culture.

“I grew up in a Blood neighborhood,” Kelley said. “I wasn’t really a gang banger, but I was in the position where I claimed a certain side of the street.”

College was not even a remote consideration. But that changed when the football recruiters came calling, and his coaches persuaded him he could compete at the top collegiate level.

Still, he had his doubts: “I was struggling so much in high school, how was I going to do well in college?”

The husband of his high school English teacher became his mentor, Kelley said — “He helped me to start believing in myself” — and with support and encouragement from UW administrators and coaches, he pulled together the necessary paperwork and was admitted to the university.

That was a watershed — and a spur.

“The people who busted their butts to get me into this university, the only way I know to repay them was by busting my butt and succeeding,” Kelley said.

He logged a 3.0 grade-point average as a freshman and finally suited up for the football team in the fall of 1999. In 2000, he played in every game, started in three and topped off the season by playing in the Rose Bowl, a few blocks from his father’s house in Pasadena.

But something wasn’t quite right.

“Football was like 24 hours a day,” said Kelley, whose GPA later slipped to around 2.5. “I wanted to do something else.”

That meant stepping beyond the comfort zone of athletics, the sphere where he had achieved the greatest success and received the richest praise.

“It’s a risk,” he said. “It’s a risk to jump outside and try something else.”

But Kelley took the risk. Five days after the Rose Bowl, he broke away from the off-season football regimen of workouts and weight training and left for South Africa. He paid for his air fare with money he received through a Mary Gates scholarship, a UW award for undergraduates to cover research expenses and other outside costs related to their education.

Kelley hooked up with the Inshinga Primary School and helped organize an after-school program in the township. The experience was another eye-opener. The children at Inshinga might eat a slice of bread for lunch, while he ate his fill on his football scholarship meal card from the UW; their impoverished families sacrificed to find the money for tuition and uniforms while he rode his athletic ability to a free education.

“It caused me to look at myself in shame,” Kelley said. “I had definite aspirations to come back and do bigger and better things.”

But Kelley is not through with college yet. In the fall, he’ll be back at the UW for a second bachelor’s degree, in sociology.

And to play football: Under the terms of his admission to the university as a partial qualifier, he forfeited his eligibility to play as a freshman, with the proviso that he could recapture that year of eligibility if he graduated on time.

After that could come professional football, Kelley said. Or law school. Or he might start his own business or non-profit organization, or accept an invitation from South African Bishop Desmond Tutu to come to his leadership institute in South Africa. (Kelley spoke at the Tutu convocation at the UW this spring.)

“South Africa is going to be somewhere in there,” he said.

Kelley lives in UW student family housing with his wife of seven months, Tonya, her two sons and a goddaughter. Tonya is his scheduler and organizer and keeps him focused, he said.

“I’ve had my difficulties,” Kelley said, “but I’ve made it through.”