Anthony in The Seattle Times: A world of Difference for Anthony Kelley

A world of difference for Anthony Kelley

Seattle Times staff reporter

http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20021225&slug=anthonykelley25

Anthony Kelley is asked what he thinks he might be doing five, 10 years from now. “I’m not predicting the future,” he said, pondering the fact that in the past two years he has completed his undergraduate degree at Washington, started graduate school, gotten married, become the head of a household that now numbers six and taken on the unofficial title of second father to almost 40 children in South Africa. “Because I never thought I’d be where I am now.”

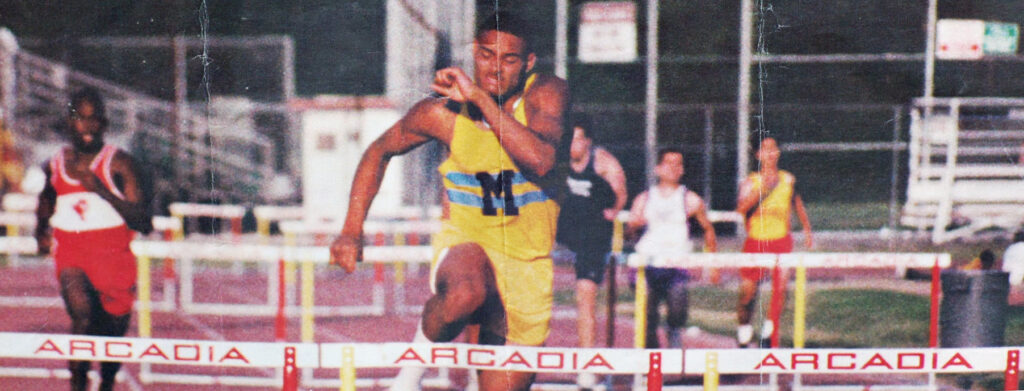

Few could have, if only because Kelley’s high-school résumé looked — on a purely superficial level — like that of someone who planned to use playing defensive end at UW mostly as a springboard to the NFL.

Kelley admits that’s what he expected, too, when he arrived at UW in 1998, albeit somewhat belatedly after running into trouble with the NCAA Clearinghouse and then being declared ineligible his first season.

“I never thought that one day I’d be looking at the NFL as an opportunity that if it happens it’s good, but if it doesn’t, it’s also good,” said Kelley, one of UW’s most heralded recruits in 1998.

He was a player so talented that Michigan wooed him with the thought of being the next great two-way phenom, a la Charles Woodson. So heavily recruited that the other school he turned down was Nebraska.

But five years later, here Kelley sits, having already accepted that the Sun Bowl next Tuesday could be the last football game he plays. And he’s more than satisfied if that is the case.

Besides, it’s almost hard to see where an NFL career would fit in amidst the trips to South Africa, the raising of four children, the pursuit of a master’s degree and a desire to right virtually every wrong he sees.

“He is very, very anxious to make a difference,” said UW Coach Rick Neuheisel.

Only now, his playing field is the entire world.

It’s a perspective that changed for good when Kelley visited South Africa in the winter quarter of 2001 as part of a UW study-abroad program, with his way paved after he earned the Mary Gates Scholarship, named after the mother of Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates.

That Kelley was even able to go on the trip was news in itself.

Kelley was an academic non-qualifier out of high school due in part to a late diagnosis of attention-deficit disorder, as well as a rocky upbringing. His mom and dad divorced when he was young, and Kelley bounced from home to home, living for a time with his mother in a car parked on the side of the freeway and attending four high schools. The last high school he attended was Muir High in Pasadena, within walking distance of the Rose Bowl.

What stability he found was in football.

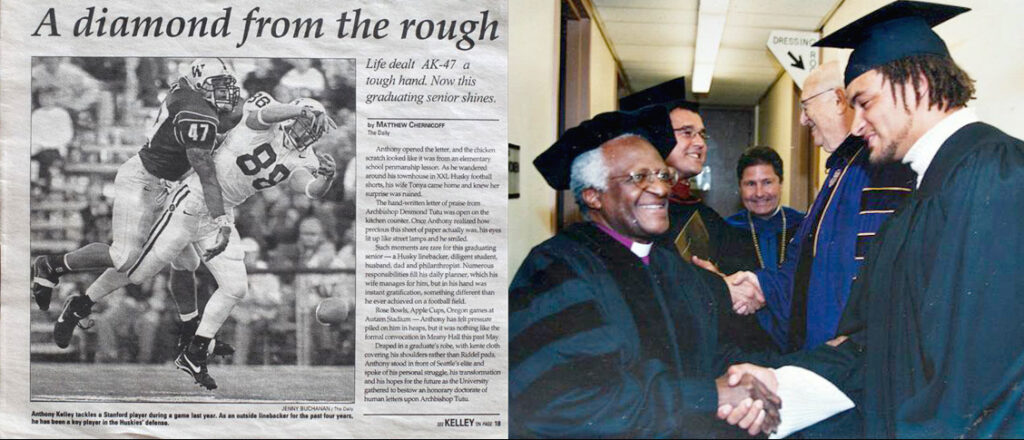

Although Kelley readily admits he thought of little but the NFL during his early years at UW, he also made a renewed commitment to academics, motivated in part to graduate in four years to earn back the year of eligibility he lost in 1998. Kelley did so by graduating last May.

“You have two ways to go when you start as low as he did,” said UW defensive coordinator Tim Hundley. “You can stay there and say school’s not that big a deal to me, or you can make it a big deal. Not a lot of guys in that situation make it a big deal. But Anthony has.”

His academic success is what led to the initial South Africa trip, which Kelley first sought mostly out of curiosity to learn more about his heritage.

Kelley left less than a week after the Huskies beat Purdue in the 2001 Rose Bowl, a game in which Kelley had five tackles and a sack and seemed to confirm his long-held belief that football was his future.

“At the time of the Rose Bowl, he couldn’t see past football,” said his wife, Tonya. “But when he came back from Africa, there was a big difference.”

Kelley said the change came from realizing that as tumultuous as his upbringing might have been, it paled in comparison to what the kids in South Africa were going through.

“He thought he had had it bad,” said teammate Jafar Williams. “But it was nothing compared to what he saw out there. It opened his eyes to a new world. He’s always had a big heart, and now he was able to go ahead and act on it.”

As part of Kelley’s study program in Cape Town, he spent time at a local school, teaching the students about sports and American culture. He quickly became infatuated with how the South Africans were excited to learn and hear what he had to say despite battling living conditions that make the worst slum in the United States look like Beverly Hills. Running water and electricity are rarities, and most families live in one-room shanties.

“They might be living in what are literally shacks, but they are doing the best they can with what they’ve got,” Kelley said. “There’s an immense pride.”

Kelley became particularly close to a 13-year-old girl named Siya, who was part of a dance group called the Ipintombi Dancers.

So Kelley helped raised more than $14,000 to bring the Ipintombi Dancers to Seattle for a six-week stay last summer. Some of the money came after Kelley mentioned his plan during a speech last May preceding an address by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who was being awarded an honorary degree at UW.

The dancers performed for church groups and graduations and took in a few major attractions. But mostly, Kelley wanted the girls to see that there could be more to their lives than what they had in South Africa.

Most of the dancers returned home last August, but Siya stayed to live with the Kelley family.

“We want her to get educated here and then take her back to South Africa where she can be a real leader in her community,” Kelley said. “She wants to be a lawyer or a doctor.”

Said Tonya Kelley: “Anthony saw himself in Siya. He just fell in love with her the first time he saw her. And when we all saw her, we saw exactly what Anthony saw.”

Kelley wants to bring more of the dancers to Seattle next summer. First, though, he’s attempting to rebuild the lives of the family of one dancer whose house was gutted by a fire. Kelley has spent the last month trying to gather clothing and other items to send to South Africa, efforts which hit a snag when the boxes were held up in South African customs.

“It’s silly,” Kelley said. “Any kind of opportunity you try to create out there, the South African government tries to take away.”

But Kelley will keep trying. He plans to take Tonya, Siya, Devan and Dominec, as well as Diamond — a 10-year-old girl who is Kelley’s goddaughter but in reality another member of the family — back to South Africa in January.

When he returns, he plans to begin full pursuit of his master’s degree in education at Washington. Kelley already has a tentative thesis, attempting to define the differences in attitude among those who live in slums in the United States and those who live in slums in South Africa.

“I think the mindset South Africans hold is a lot stronger than ours here as far as taking advantage of what opportunities you have,” he said.

Kelley said he wants to find out “why don’t we have that same mindset here as Americans?”

Most important, though, he wants to be a good role model for the four children in his family, as well as the other 38 Ipintombi Dancers that Kelley says “makes me feel like I have 42 kids.”

“My family had our difficulties and shaped me to understand as a father what I don’t want my kids to go through,” he said. “We’ve got a real diverse bunch of kids here, so many different personalities. But they all come together to do a lot of great things.”

Kelley hasn’t completely given up on football, though he readily admits that his off-field interests the past two years probably haven’t helped his play.

“The first year he went (to South Africa), there’s no question it got such a hold of him that it did take away from what he was capable of being as a football player,” Neuheisel said. “Going back last year, he was able to put everything into perspective in how it all fits into place in his life. He’s been a much more focused and driven athlete this year and consequently he’s been a much more productive football player. He’s got a chance (in the NFL). The NFL is full of overachievers, and he’s an overachiever in a lot of ways.”

The money that an NFL career would provide, Kelley says, would be nice. The family lives in UW student housing on Kelley’s scholarship check and Tonya’s savings.

But if he’s not drafted — which seems the more likely scenario given that Kelley had 10 tackles in 12 games this season, though five were sacks — Kelley says he’ll hang up his cleats.

“If it doesn’t happen, it won’t be the end of the world for me anymore,” Kelley said.

No. Just the beginning of a new one.