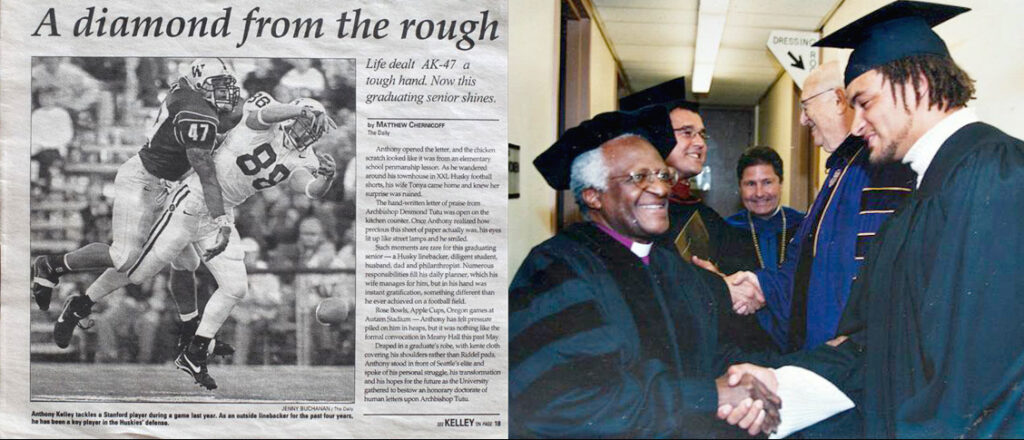

Anthony in The Seattle Times: Kelley Finally Hopes To Put Himself In Position To Excel

Kelley Finally Hopes To Put Himself In Position To Excel

Seattle Times Staff Reporter

http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19990404&slug=2953321

A WHIRLWIND HIGH-SCHOOL career kept Anthony Kelley from putting down roots, but the Washington Husky could see steady growth at outside linebacker.

He’s here. He’s there. He’s gone. He’s back.

Settle in, Anthony Kelley, the Washington football coaches tell him. Chill. Find a niche and run with it, and then think about moving on to something else.

As Rick Neuheisel tells it, Kelley is like the proverbial blind dog in a meathouse, unsure what to lunge at next. Every position on the Husky football team, he thinks could be his.

“He wants to try a little of everything,” said Neuheisel, the UW coach. “What we’ve got to do is get him to focus on one job. And then we’ll see.”

Perhaps it’s natural for Kelley to envision himself as the next notable two-way player in college football. His high-school years were the equivalent of one-platoon football – all over the place.

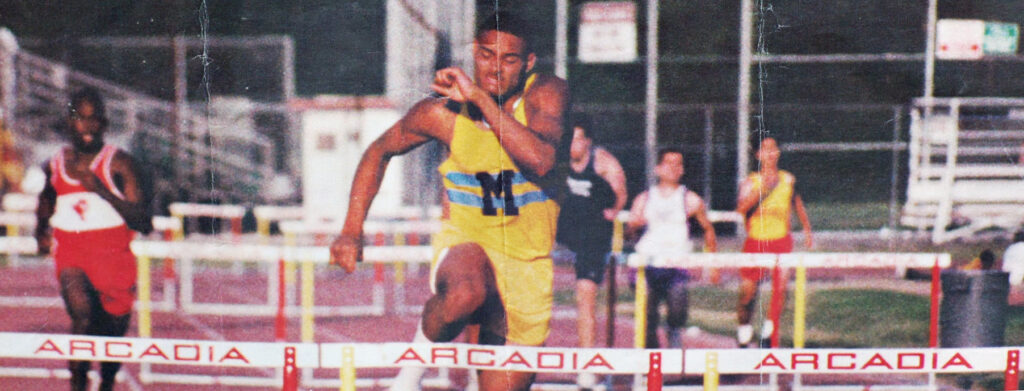

When the Huskies locked onto him, they caught only the snapshot of Kelley at John Muir High in Pasadena, where, at 6-foot-3 and 215 pounds, he played linebacker and tight end, and in track season, devoured the 110-meter high hurdles in 14.2 seconds.

There was another side to Kelley, the one that never had a chance to put down roots. His mom and dad had split up years before, Mary Jo now living in Flint, Mich., his father, Anthony Sr., in Pasadena.

Kelley clicks off the high schools he attended in a two-year period: West Covina, John Muir and Marshall of Pasadena, a fourth one in Flint. There were family problems, and the younger Kelley went where he was needed.

“Every time I’d get myself established,” Kelley said yesterday after the Huskies’ third spring workout, “I’d have to up and leave. Somethin’ was goin’ on.”

By 1997, his high-school coaches had convinced him that his football potential could take him to college, if only he could put a rush delivery on academics. So Kelley took eight classes his senior year and thought he was in.

The choices were Washington, Nebraska and Michigan, just off a national-championship season. On his trip to Ann Arbor, Kelley chatted up Heisman Trophy winner Charles Woodson on the topic of playing both ways. And then he committed to the Wolverines.

“My mom was there, it sounded good,” Kelley said. “It seemed like a good idea.”

The Huskies eventually won his signature, but the quest was only beginning. The NCAA Initial-Eligibility Clearinghouse struck down one of his classes, leaving him short of the required core of 13.

“All the high schools I went to, they (the Clearinghouse) needed to get letters, from teachers, athletic directors, principals,” Kelley said. “We had to get transcripts, unofficial transcripts.”

Finally, Kelley sought a waiver that would allow him to meet the NCAA halfway. It would accept the Proposition 16 mandate of ineligibility as a freshman, but at least it would let him practice. Kelley had to write a letter on his own behalf.

“I didn’t write a sob letter about how rough it was growing up,” Kelley said. “I was a kid that didn’t have the opportunity. I didn’t have tutors to help me with my classes. I was overwhelmed with a lot of hard things. If I’d had the help, I’d have had a chance.”

Said his father, “A lot of schools are better off than other schools. John Muir is in a very poor neighborhood. Those kids barely have books. They don’t have college-preparation classes.”

The NCAA granted Kelley the waiver. He arrived three games into last season – too late to play, realistically, but not too late to succeed in school.

“I’m doing better in college than I did in high school,” Kelley said. “I’ve got about a 2.8 grade-point average.

“The team, I’m doing it for the team. Because I want to let them know I’m not here just for sports. To let them know I’m serious about this. This is my one golden opportunity, and I want to take it to its limits.”

Kelley will play next fall, probably a lot. Neuheisel only has to convince him it will be at outside linebacker, which is OK by Kelley, and not at some of the other positions Kelley has eyed since he got here.

“Anthony needs to be in one place,” Neuheisel said. “His mind is all over the place. You love that exuberance, but you also want to channel it.”

Kelley is nothing if not exuberant. Yesterday, he took on classmate Jerramy Stevens, a tight end, and when they were done grappling, Kelley was running a lap’s punishment.

“The Huskies aren’t on our schedule next year,” Neuheisel observed dryly.

“I won’t react like that next time,” Kelley promised. “I wanted to let him know, when you’re on offense, you’re not my friend when I’m on defense.”

It’s a simple equation, as basic to Kelley as availing himself of what’s before him.

“All the stuff I’ve been through, I don’t regret none of it,” he said. “I wouldn’t be as strong a person as I am now. I wouldn’t be able to appreciate all the gifts I’ve got, the opportunities I’ve got.”